In his time at Yale, senior Barkotel Zemenu has embraced profound questions about the universe and personal bonds at the heart of one-on-one conversation.

Four years ago, Zemenu entered the vortex of Yale undergraduate life with a passion to study history. Perhaps he might teach it someday, he thought. Instead, he emerges this spring as a promising particle physicist who has already contributed to cutting-edge research and interned at an international physics project in Germany and at a premiere astrophysics institute in Israel.

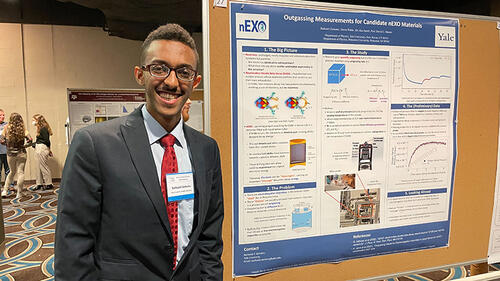

Zemenu has gone from crabbing about the undergraduate foreign language requirement to enthusiastically developing a knowledge of Hebrew, Arabic, Mandarin, and Greek, in addition to English and Amharic, his native language; he’s traveled across the United States to academic conferences, giving high-level physics presentations on neutrinoless beta double decay; he’s even found the time to co-teach a class for middle schoolers on the meaning of life.

Not bad for a guy who spent his first year as a Yalie doing middle-of-the-night Zoom classes from a hotel lobby — where the wifi was stronger than at his parents’ house — in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

“So many of these things were unexpected, but I’m grateful for all the pivots,” he said, basking in the afternoon sun from a bench outside Pauli Murray College, a frequent stopping place between his physics home base at Wright Lab and his dorm room at Hopper College. “I had not expected college to be a place where I pivoted so much.”

Zemenu picked Yale after participating in Yale Young Global Scholars, a summer program that brings American and international high school students together and introduces them to the Yale campus. But then came Zemenu’s first pivot.

He spent his first year of college living in Ethiopia with his parents, after the COVID-19 pandemic led Yale to make all classes remote as a public safety measure. In those early days, Zemenu would set an alarm for the middle of the night, take a cab to a nearby hotel with a strong wifi connection, and dial into his online classes from the hotel lobby. He became such a frequent visitor that the hotel’s employees would recognize him and leave him alone to work undisturbed.

“It was just business as usual,” he said. “Now, any time I find myself complaining about the walk up Science Hill, I remind myself what a luxury it is to be here, in person.”

Once Zemenu got to New Haven, the pivots began to pile up. He leaned into physics, particularly the unseen world of dark matter and neutrinoless double beta decay — a theoretical nuclear process that, if proven, could shake up the Standard Model of Physics.

He also delved into the writings of revered 20th century physicist Richard Feynman, and a biography of 19th century Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell. Zemenu came to the notion that it would be valuable to have one area of deep expertise that is informed by a broad range of studies. He chose physics as his deep dive.

“We’ve been lucky to have Barkotel as a member of our research group over the past three years, where he’s been studying detector technologies aimed at figuring out why there is matter, rather than antimatter, in the universe,” said David Moore, an associate professor of physics in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “In addition to his packed academic schedule and leadership activities in the department, Barkotel has been a key contributor to our research.”

“While we are sad to see him go, we are looking forward to seeing his many accomplishments in the future.”

Zemenu spent part of a summer at the Weizmann Institute of Science, near Tel Aviv, where he wrote a 20-page white paper on his research developing a novel program to automate the identification of variable stars from a telescope image. He spent part of another summer in Germany, at the Munich Center for Quantum Science and Technology, where he studied quantum gravity. He’s also attended science conferences in New Orleans, Honolulu, Washington, D.C., and Minneapolis.

Meanwhile, his list of honors grew along with his frequent flier miles: the Jocelyn Bell Outstanding Leadership Scholarship, the Sigma Pi Sigma Leadership Scholarship, a Rosenfeld Science Scholar award, an American Physical Society Top Presenter award.

“I remain extremely interested in this idea of dark matter and dark energy,” he said. “We don’t know what the majority of the matter in the universe is actually made of. We’ve quantified it, but we don’t know what it is. That’s a question I’d like to see answered in our lifetime.”

While open to pivoting yet again, Zemenu intends to pursue that question after leaving Yale and entering graduate school at Stanford. He’ll also pursue a more recent passion: accessing the deeper, more meaningful interactions that emerge when you communicate with people in their native language.

Much to his surprise, he discovered at Yale that he has a great facility for reading, writing, and speaking other languages. He’s written poetry in Hebrew, for instance, and shared a laugh with a family member of a friend by explaining, in Chinese, that his preferred level of spice is “scared of not-spicy food.”

“Speaking to someone in their own language opens a different door to aspects of themselves that you won’t learn about otherwise,” Zemenu said. “That was the part about languages I hadn’t realized. It isn’t purely academic. It’s about relationships.”

That may be his biggest pivot of all, he said.

This story was originally published in Yale News on April 30, 2024.